- A hundred and nineteen things a punkist should know. [http://www.punk.ist]

- Firewood will save the West. [Unherd] “Our dysfunctional society must return to the hearth.”

- ‘Luddite’ Teens Don’t Want Your Likes. [NYT] “When the only thing better than a flip phone is no phone at all.”

- Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. [Nature] “We find that papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions. Overall, our results suggest that slowing rates of disruption may reflect a fundamental shift in the nature of science and technology.”

- Assessing the effectiveness of energy efficiency measures in the residential sector gas consumption through dynamic treatment effects: Evidence from England and Wales. [Energy Economics] “This paper disentangles the long-lasting effects of energy efficiency technical improvements in UK residential buildings. The installation of energy efficiency measures is associated with short-term reductions in residential gas consumption. Energy savings disappear between two and four years after retrofitting by loft insulation and cavity wall insulation, respectively. The disappearance of energy savings in the longer run could be explained by the energy performance gap, the rebound effect and/or by concurrent residential construction projects and renovations associated with increases in energy consumption. Notably, for households in deprived areas, the installation of these efficiency measures does not deliver energy savings.”

- Mapping Four Decades of Appropriate Technology Research: A Bibliometric Analysis from 1973 to 2021. [Sains Humanika] “The purpose of the study is to examine the publication trends, collaborative structures, and central themes in appropriate technology studies.”

- Life in the Slow Lane. [Longreads] “Cooking all day while the cook is away. How the slow cooker changed the world.”

- Can a Robot Shoot an Olympic Recurve Bow? A preliminary study. [National Taiwan Normal University]

- Amnesty, Yes—And Here is the Price. [Charles Eisenstein] “The invisible workings of the Covid machine must be laid bare if we are to prevent something similar from happening again.”

- Reduce, re-use, re-ride: Bike waste and moving towards a circular economy for sporting goods. [International Review for the Sociology of Sport] “This study focuses on the bike and its role in global waste accumulation through various forms of planned obsolescence.”

- Civilian-Based Defense: A Post-Military Weapons System. [International Center on Nonviolent Conflict]

- Millionaire spending incompatible with 1.5 °C ambitions. [Cleaner Production Letters]

- Radical online collections and archives. [New Historical Express]

No Tech Reader #35

Does covid cause brain damage?

“The latest in the long succession of attempts at maximizing people’s fear of covid is the claim that it causes brain damage. And not just in those who have spent time in the ICU, in everyone, even if all they had was a mild cold. The claim is currently doing the rounds on social media (apparently alarmist propaganda only counts as misinformation if it’s going against the dominant narrative). The assertion comes from a paper that’s recently been published in EClinicalMedicine (a daughter journal of The Lancet). The paper is actually quite illuminating about the current state of medical research, so I thought it would be interesting to go through it in some detail…”

“To me, the main lesson here is that we currently live in a world where junk science goes unquestioned and gets published in peer-reviewed journals as long as it feeds in to the dominant narrative. If this study had been claiming, say, that face masks didn’t work, then it would remain stuck at the pre-print stage forever, or, if it ever did get published, it would immediately have been retracted. It has become blatantly obvious over the past year and a half that it is not primarily the quality of studies that determines where and whether they get published, but rather their acceptability to the powers that be.”

Read more: Does covid cause brain damage?, Sebastian Rushworth, July 26, 2021.

We believe in Science

Theoretically, science is the contrary of religion because, while the latter is dogmatic, science should be anti-dogmatic, based on rationality and on an objective and empirical methodology. However,… science contributes to create the cultural system whereby we live and that gives meaning to our reality, which is based on some basic assumptions/beliefs: our “faith”.

The core of science has embodied the heritage of Christianity and Hebraism and, in a different way, could be practiced as a religion from many people. For western religions, the past was evil, the present redemption and future heaven. For science the past is ignorance/superstition, the present consists of progress using the tools of science, and the future consists in the positivistic promise of a sort of heaven in the real world.

Quoted from: Aillon, J. L., and M. Cardito. “Health and Degrowth in times of Pandemic.” Visions for Sustainability 14 (2020): 3-23.

Full issue of the magazine (Health and Degrowth Special).

Image by Kārlis Dambrāns – Mobile World Congress 2018, CC BY 2.0.

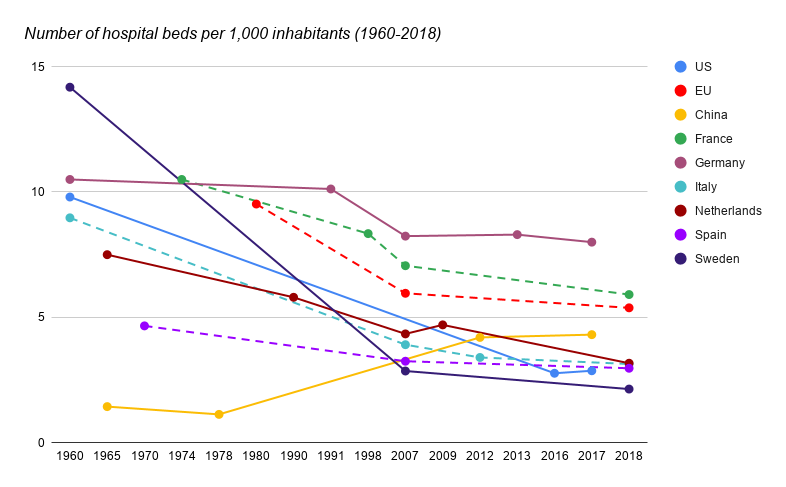

Number of Hospital Beds per 1,000 Inhabitants (1960-2018)

Corona restrictions around the world are primarily aimed at not overwhelming hospital capacity. But hospital capacity is not what it used to be. In the 1960s and 1970s, the US and many European countries had around ten hospital beds per thousand inhabitants. Nowadays, the US has less than three, while many European countries have less than five.

Hospital beds are defined as beds that are maintained, staffed, and immediately available for use. Total hospital beds include acute care beds, rehabilitative beds and other beds in hospitals. [Read more…]

Frugal Innovation for Global Surgery

Limited or inconsistent access to necessary resources creates many challenges for delivering quality medical care in low- and middle-income countries. These include funding and revenue, skilled clinical and allied health professionals, administrative expertise, reliable community infrastructure (eg water, electricity), functioning capital equipment and sufficient surgical supplies. Despite these challenges, some surgical care providers manage to provide cost effective, high quality care, offering lessons not only for other low- and middle-income countries but also for high-income countries that are working towards increasing value-based care. Examples would be how to optimise the consumption of resources, and reduce the environmental and public health burden of surgical care.

Owing to the liberal utilisation of capital equipment and single-use supplies, surgical care in high-income countries is increasingly recognised as a significant source of greenhouse gases and other environmental impacts that adversely affect human health. Regulations require many potentially reusable supplies and drugs to be discarded after single use. Supply manufacturers may label drugs or products as single-use to increase profit, reduce liability or facilitate regulatory approval. Many high-income countries struggle to increase the value of care while maximising quality and outcomes, and minimising cost and resource use.

For most high-income countries, cataract surgery is the highest volume and most expensive surgical procedure (in aggregate) in all of medicine. Studies analysing global cataract care found few differences in outcomes, such as surgical infection, despite large differences in carbon footprint and cost. A single cataract procedure in the UK emits an estimated 180kg CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalents) whereas the same surgery with similar outcomes in India emits only 6kg CO2e, 5% of that in the UK.

Source: Steyn, A., et al. “Frugal innovation for global surgery: leveraging lessons from low-and middle-income countries to optimise resource use and promote value-based care.” The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 102.5 (2020): 198-200. [open access]